FOOT DEFORMITY

A "foot deformity" is a disorder of the foot that can be congenital or acquired.

Common Foot Deformities

Competency:

The resident should be able to recognize most common foot deformities, to differentiate them from more rare and severe deformities and be able to guide the parents through treatment alternatives and to stress referral to specialists as needed.

Case:

You are a resident at the GCN performing the first physical exam on a full term Hispanic male infant. On your exam of the extremities you find the deformity shown below.

What are you telling the parents when you bring the baby boy into the room after you have finished your evaluation?

• What are the common forms of foot deformities?

• How do you diagnose the different deformities?

• How do you differentiate clubfoot from Metatarsus adductus (MTA)?

• Why is it crucial to differentiate between Calcaneovalgus and Congenital Vertical Talus (CVT)?

• Why is it crucial to distinguish a Metatarsus varus from Metatarsus adductus foot?

• How do you clinically distinguish a severe form of metatarsus adductus from a clubfoot?

• What is the current management of those foot deformities?

• What is the current management of those foot deformities?

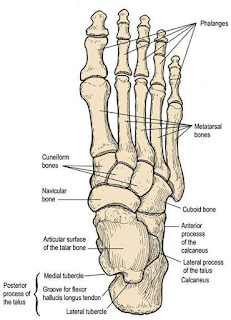

The foot can be divided into three anatomic regions (Figure 1): the hindfoot or rearfoot (talus and calcaneus); the midfoot (navicular bone, cuboid bone, and three cuneiform bones); and the forefoot (metatarsals and phalanges).

Most foot deformities are minor and have a favorable prognosis. However, some may be the first sign of a significant problem.

A thorough physical examination of ankle, hindfoot and forefoot regarding position, alignment and flexibility of each segment helps you to identify and distinguish between the more common

deformities. A thorough examination includes assessment of vascular, dermatologic, and neurologic status of the lower extremities, and observation, palpation, and evaluation of joint range of motion in both feet:

• Simultaneous observation of both feet

• Look for skin folds or creases

• Move all ankle joints through there ROM and assess them

• Assess skin color, temperature, capillary refill and pulses

What are the most common foot deformities and the important differential diagnoses?

Clubfoot (Talipes Equinovarus)

Incidence 1 - 2 per 1000 live birth, in 50 % bilateral, male to female ratio is 2.5: 1, more dominant in Hispanic Population.

The exact patho mechanism responsible for the malformation is still unknown. Theories advocate that the clubfoot is the result of intrauterine mal development of the talus that leads to adduction and plantar flexion. The milder forms are related to intrauterine molding. The rigid form are either idiopathic or teratologic with the latter group associated with syndromes like myelodysplasia, arthogryposos etc.

The risk of occurrence increases with first degree affected relatives to 2-4 % and if parents and sibling are affected up to 25 %.

How do you diagnose a clubfoot?

The diagnosis is made clinically. You will find these three components when examining the affected foot:

• Extreme plantar flexion of the ankle ( equinus )

• Medial angulation of the hindfoot ( varus )

• Adduction and supination of the forefoot ( metatarsus adductus)

All of these criteria must be present to make the diagnosis.

On inspection, the foot appears "down and in" and smaller, with a flexible, softer heel because of the hypoplastic calcaneus. The medial border of the foot is concave with a deep medial skin furrow, and the lateral border is highly convex. The heel is usually small and is internally rotated making the soles of the feet face each other in case of bilateral involvement.

How do you differentiate clubfoot from Metatarsus adductus (MTA)?

On testing of a clubfoot there is a pronounced Achilles tendon tightness and only limited dorsiflexion which you do not find with MTA.

Radiography is usually not required.

What is the current management of patients with clubfoot and to whom should the patient be referred ?

It is crucial to distinguish between extrinsic supple type, which is a severe positional or soft tissue deformity that can be manually partially corrected and intrinsic (rigid) type, where manual reduction is impossible.

The type of clubfoot determines the specific therapy:

• Extrinsic clubfoot can be treated by serial casting

• Intrinsic clubfoot may require surgery

Patient should be referred to a Pediatric Orthopedic Specialist.

Plaster casting should be attempted on all clubfeet, supple or rigid, as soon as possible. Serial casts should be continued for about three months until correction is achieved. The cast needs to be changed twice weekly and than in one to two weeks intervals. If the foot is resistant to this treatment surgical correction is required when the child reaches 4 – 6 months of age.

Persistent cast treatments by experienced clinicians have been reported to be successful in most patients. But if a complete correction can not be reached, surgery by a specialist in pediatric foot deformities should be considered.

It is important to know that with a clubfoot the child has not only misshaped and misaligned tarsal bones but the bones are also reduced in size as is the musculature in the posterior compartment of the leg.

Therefore it is important to explain to the parents that by unilateral involvement the affected foot will always be smaller than the unaffected foot.

Furthermore in evaluating children with a rigid club foot it is important to rule out possible associated syndromes like myelodysplasia, arthogryposos etc.

Calcaneovalgus foot

This deformity is located in the tibiotalar joint and occurs in about 5 % of all newborns affecting more female than male mostly as a result of intrauterine molding.

How do you diagnose a Calacaneovalgus foot?

Clinically you will find that the foot appears flat, the heel bone is angled away from the midline and the ankle rests in dorsiflexion so that the dorsal surface is positioning up against the anterior surface of the tibia. The ankle generally can be plantarflexed to only 90

degrees or less. In mild case the foot is flexible and easily manipulated into plantar flexion in more severe cases this motion is limited. Radiography can confirm the clinical diagnosis but is not obligatory.

What is the current management of a Calcaneovalgus foot ?

Generally the treatment depends on the severity of the deformity. Mild cases can be treated with stretching exercises performed with every diaper change bringing the foot passively in plantar flexion and slight inversion for a count of 10, repeated three times.

If stretching fails after 1- 2 months or in more moderate cases splinting is indicated to prevent dorsifelxion. These children should be referred to an Orthopedic Specialist.

For severe deformities serial casting for up to three months is needed followed by a maintenance therapy consisting of nightly splinting for 2 – 10 weeks.

Congenital vertical talus ( CVT, Rocker-Bottom foot)

This is a rare deformity which diagnosis is frequently delayed because CVT is often confused with calcaneovalgus.

It is a rigid deformity, as opposed to a flexible calcaneovalgus foot, so it does not respond to stretching and, in most cases, requires surgery.

How do you diagnose Congenital vertical talus foot?

The talus is positioned in plantar flexion and the talonavicular joint is dislocated and positioned dorsally on the talus.

The foot examination usually reveals a rigid foot with a convex plantar surface, and a deep crease on the lateral dorsal side of the foot. The ankle joint is plantarflexed, while the midfoot and forefoot are extended upward. The dislocation is difficult to palpate but the prominence of the talar head is obvious.

Radiographic evaluation in AP and lateral view of the foot in dorsiflexion and maximum plantar flexion will be helpful.

Why it is so crucial to differentiate between Calcaneovalgus and CTV?

In a patient diagnosed with CTV is important to examine the entire child, looking for other abnormalities, such as arthrogryposis (multiple joint contractures present at birth) and meningomyelocele as those underlying diseases might be present in up to 60 percent of children with congenital vertical talus.

What is the current management of CTV ?

Conservative therapy can assist in stretching the forefoot and hindfoot, but surgery is needed in most cases. Surgery is complex,

requiring correction of all three planes and should be performed by a specialist in pediatric foot deformities.

Metatarsus adductus

Metatarsus adductus is a very common forefoot adduction deformity in infants occurring in one to two cases per 1,000 live births. It is defined as a transverse plane deformity in the (tarsometatarsal) joints where the metatarsals are deviated medially. It results from intrauterine molding of the forefoot, with the forefoot compressed into adduction.

How do you diagnose a Metatarsus adductus foot?

Diagnosis is made clinically via physical exam of the affected foot. You will find that the forefoot is medially deviated causing the lateral border of the foot to be curved, giving the foot a kidney bean shape. In infants a simple test named “V” can raise suspicion of Metatarsus adductus. In this test, the heel of the foot is placed in the "V" formed by the index and middle fingers, and the lateral aspect of the foot is observed from a plantar side for medial or lateral deviation from the middle finger. Radiography is usually not required.

The forefoot in metatarsus adductus can be corrected passively or actively and can be often overcorrected into abduction. Active correction occurs with digital stimulation of the lateral border of the foot.

Treatment is successful in 90% with passive stretching exercises, with the hintfoot stabilized with one hand and lateral pressure applied at the fist metataseal head.

If that treatment fails by age 3 to 4 months or the deformity is more rigid the child needs to be referred to an Orthopedic Specialist and serial casting may be needed as excessive compensation at the level of the mediotarsal joint can lead in the future to the development of bunions, hammertoes, and other disorders.

Only a small percentage of children will need surgical repair, when the deformity is not resolved by age of 18 months.

Metatarsus varus

Metatarsus varus occurs in about 1 to 1000 live birth , with a recurrence risk within the family of 1 to 20/ 1000.

Congenital metatarsus varus is a medial subluxation of the tarsometatarsal joint, with adduction of the metatarsals.

Metatarsus adductus needs to be distinguished from Metatarsus varus as the first one corrects spontaneously whereas Metatarsus varus will without active intervention progress when walking is initiated.

How do you diagnose a Metatarsus varus foot?

Clinically you can distinguish Metatarsus varus by the following features encountered during the physical exam:

• a deep vertical skin crease on the medial aspect of the foot at the tarsometatarsal joints

• prominence of the base of the fifth metatarsal

• convexity of the lateral border of the foot

• inability to passively align the forefoot with the heel

Radiography may be helpful in distinguishing a Metatarsus varus from a severe form of clubfoot.

A severe form of metatarsus foot has the ability to dorsiflex the ankle in neutral position whereas the clubfoot cannot.

What is the current management of a Metatarsus varus foot?

You should refer the patient to an orthopedic surgeon as soon as the diagnosis is made as Metatarsus varus results in progressive deformity when walking is initiated.

Serial solid casting is the initial treatment with weekly cast changes in children under two months of age and biweekly with older children lasting up to three months.

The successful correction is achieved when the lateral border of the foot is straight, the forefoot rests in neutral position and the foot can be overcorrected passively.

To maintain the correction a subsequent treatment with a removal cast used at night or a plastic orthotic with a shoe for a minimum of 4 month is needed. This is usually combined with a stretching exercise program.

Indication for operative treatment is given if the correction is not achieved after 3 months casting (children presenting after 8 months of age are known to have a higher failure rate) or if a child presents having a rigid deformity after the age of two years.